Hello everyone, and welcome back to our feature, “Ingredients Under the Lens”!

There’s a scent in the July air that speaks a thousand words. It’s the sweet and slightly tangy aroma of fruit at its peak expression; for example, juicy peaches, velvety apricots, and the intensity of berries. Instinctively, we want to use them to decorate a tart or for a refreshing fruit salad. However, what if we paused for a moment and looked closer?

We would discover that every fruit is a small biochemistry lab, governed by precise laws. Understanding these laws means moving from “let’s hope it doesn’t turn brown” to having total control of the result. Ultimately, it’s about using fruit not as a simple decoration, but as the stable, beating heart of our desserts.

Therefore, today we go beyond appearances. We are putting this wonderful gift of nature under our lens in order to understand how science can help us elevate it to its fullest potential.

The freshness of fruit combined with the precision of science: the first step towards perfect desserts. #BakingScience #HonestOven

The Technical Eye: An In-Depth Analysis

Fruit is a complex living organism. In essence, it is a treasure trove of sugars, water, acids, vitamins, and, above all,structural compounds that determine its behavior during preparation.

Pectin: The Natural Architect

Pectin is a polysaccharide (a complex sugar) found in the cell walls of plants. You can think of it as the “cement” that holds the cells together, giving the fruit its texture and structure. Its concentration, for instance, varies. It’s high in slightly under-ripe fruit, which is why jams are often made with fruit that isn’t too mature. As a result, the pectin degrades as the fruit ripens, making it softer. Furthermore, its extraordinary gelling power is activated only under specific conditions. Specifically, it requires heat, an acidic environment, and the presence of sugar to create a three-dimensional network capable of trapping water.

Osmosis and Maceration

When we sprinkle fruit with sugar, we trigger a fascinating physical phenomenon called osmosis. The fruit’s surface acts as a semi-permeable membrane. Essentially, the sugar creates an external environment with a high concentration of solutes. This new environment then ‘draws’ water from inside the fruit’s cells—where the concentration is lower—to rebalance the system. As a result, water is released, creating a delicious syrup while the fruit itself partially dehydrates, concentrating its flavor.

Acidity (pH): The Regulator of Taste and Color

Acidity is a fundamental technical element. Firstly, it balances sweetness, enhancing the fruit’s aromatic complexity. Secondly, as we’ve seen, it’s crucial for inhibiting enzymatic browning and for activating pectin. Finally, it also stabilizes the color of many red fruits (whose molecules, anthocyanins, are sensitive to pH), keeping them vibrant and bright.

Enzymatic Browning

Have you ever wondered why a cut apple or peach turns brown in minutes? Indeed, the culprit is an enzyme called polyphenol oxidase (PPO). When we cut the fruit, we break its cell walls. Consequently, this brings the enzyme into contact with oxygen from the air and with polyphenols in the fruit. This reaction then produces melanins, which are the dark pigments we see. In order to stop this process, we must block one of the key actors. For example, we can inactivate the enzyme with heat, lower the pH with an acid like lemon juice, or limit oxygen contact by submerging the fruit in syrup.

Science at work: a few minutes of rest and osmosis unleashes an explosion of fruit flavor. #BakingScience

In Practice: Problems and Scientific Solutions

Armed with this knowledge, we can tackle practical problems with effective, informed solutions.

Problem: “The fruit on my tart turns dark and sad.”

Solution: Before arranging it on the tart, brush the cut fruit with lemon juice diluted in a little water. Because of this, the citric acid will block the browning enzyme and keep the colors vibrant. Additionally, a layer of cold-process glaze after baking will create a barrier against oxygen.

Problem: “I want to make a fruit insert for a modern cake, but I’m afraid it will release water and ruin everything.”

Solution: To solve this, cut the fruit into small pieces and cook it briefly in a saucepan with a spoonful of sugar and a few drops of lemon juice. The heat and acidity will activate the fruit’s natural pectin. This, in turn, will bind the excess water, creating a stable compote (coulis) that is perfect for inserts or freezing.

Problem: “My jams are sometimes runny, sometimes perfect. Why?”

Solution: Of course, it depends on the pectin and acid content of the fruit you use. For best results, use fruit that isn’t overly ripe. If you use very sweet and low-acid fruit like peaches, then always add lemon juice. Not only will this help the pectin do its job, but it will also balance the taste.

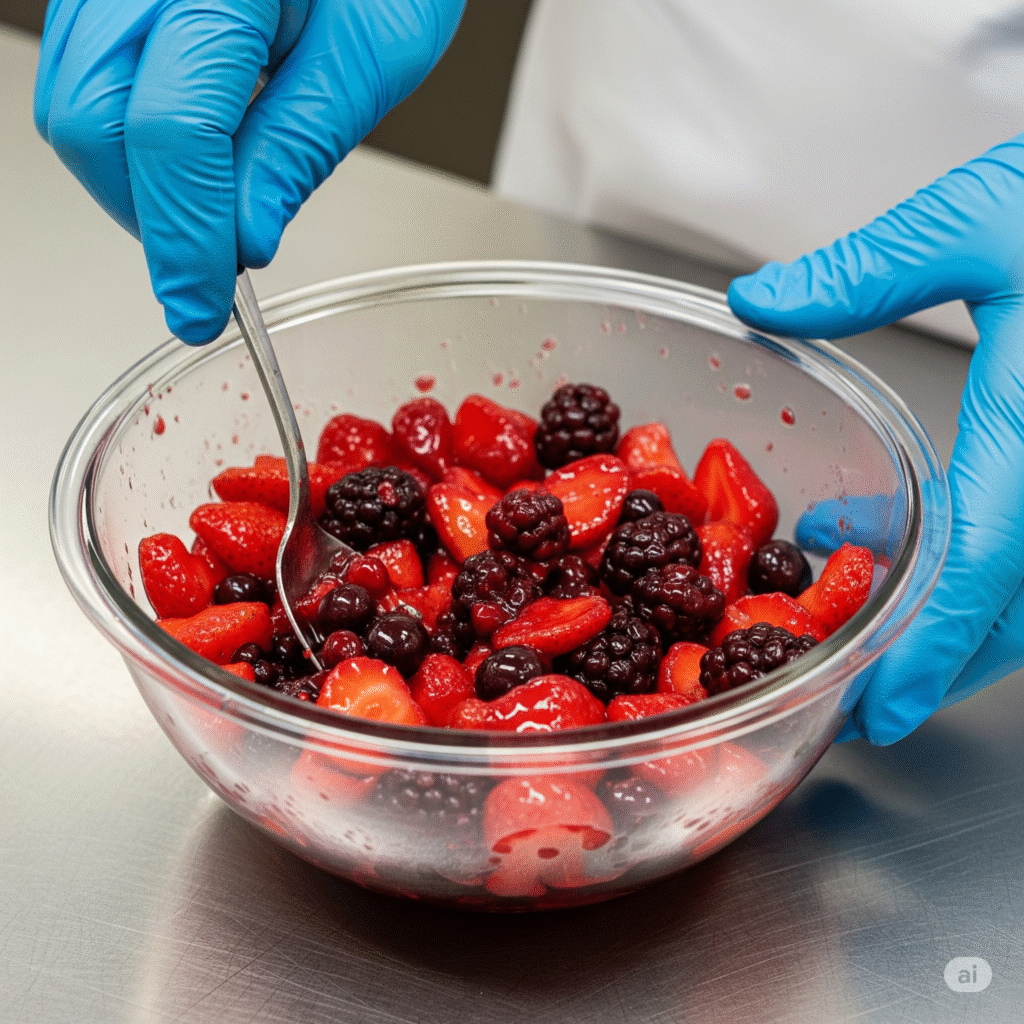

Pro Tip: The Perfect Maceration to Enhance Flavor

Do you want an explosion of taste? Take some berries or strawberries, chop them, and add about 10% of their weight in sugar and a little lemon juice. After mixing, let it rest in the fridge for an hour. Through osmosis, an incredibly aromatic natural syrup will form, which is perfect for topping ice cream, yogurt, or panna cotta.

Conclusion

Treating fruit with scientific awareness opens up a world of possibilities. In conclusion, it’s no longer just an ingredient to be placed on a dessert. Instead, it is a versatile and fascinating material with which to build textures, stabilize preparations, and enhance flavors.

The next time you hold a peach or a handful of blueberries, I hope you’ll look at them with new eyes. You will see not only their beauty, but also the incredible potential that knowledge allows you to unleash.

Happy summer experimenting!

Katia Oldani, Biologist Pastry Chef