In the collective imagination of modern baking, especially in the world of pizza, a specific aesthetic dominates: that of “contemporary pizza”. It’s an aesthetic defined by pronounced ‘cushion-like’ crusts (‘cornicioni a canotto’), which are light and characterized by a wide, almost ethereal crumb.

This shape is the direct result of a precise technical choice: high hydration. To achieve this result, one must master high hydration pizza dough.

For years, “safe” dough management hovered around 60-65% water based on flour weight. Today, experimentation constantly pushes this threshold beyond 70%, 80%, and even 90%. But why do we do it? And, above all, what happens at a chemical, physical, and biological level when we push water to these levels?

The common mistake is to think of water merely as a “diluent”. The reality, as we will see, is very different. Water is the universal solvent for biological reactions (fermentation), the reagent in the hydration of macromolecules, and the primary plasticizer of our dough.

Let’s analyze the ingredient that determines the entire process: Water.

PART 1: The Home Baker’s Guide to High Hydration Pizza Dough

For home bakers, tackling a high hydration pizza dough (over 70%) is often frustrating. The dough is sticky, elusive, seems to have no “strength”, and collapses on the counter. To manage it, we must understand the two roles of water.

- “Bound” Water vs. “Free” Water

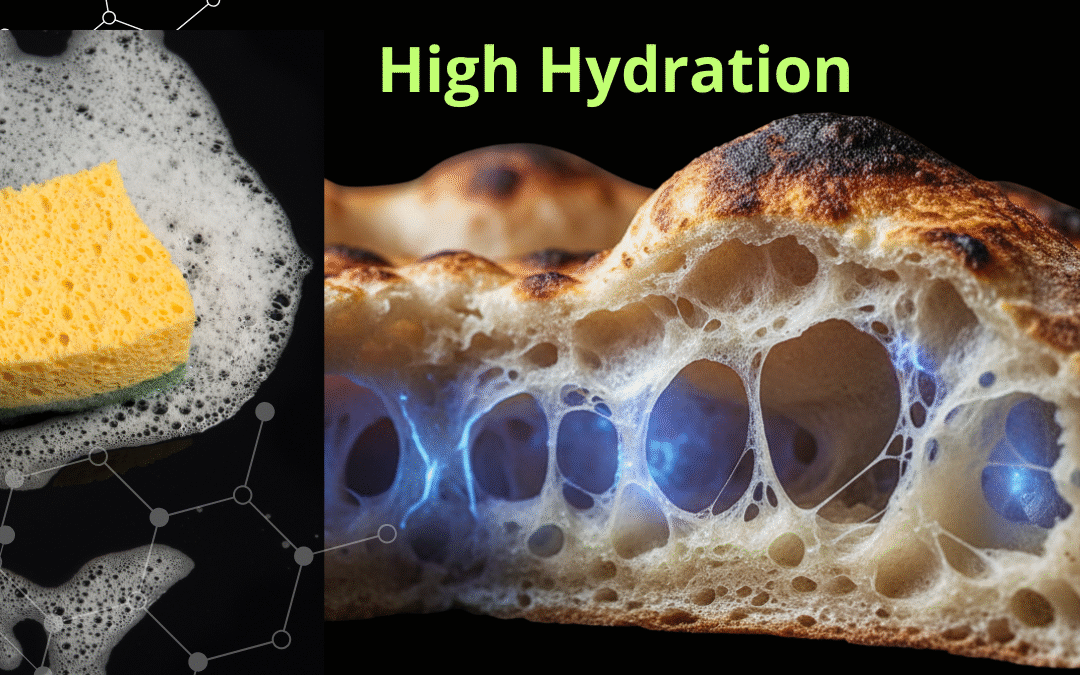

Imagine flour as a packet of microscopic sponges. These “sponges” are the proteins (gliadin and glutenin) and starches (especially damaged ones).

- Bound Water (or Hydration Water): This is the first water we add. It is literally “captured” by the proteins and starches, which swell. This water is no longer available; it’s part of the structure.

- Free Water: This is all the water we add after the sponges are saturated. This water remains “free” in the dough, acts as a lubricant between the gluten strands, and makes everything sticky.

The difficulty isn’t adding water, but giving the flour time to bind it. High hydration is, first and foremost, a matter of patience.

- Gluten: From Elastic Net to Extensible Network

At low hydrations, gluten forms a dense, strong, highly elastic network (like a rubber band). If you inflate it (with gas), it resists and then tears. At high hydrations, the “free water” inserts itself between the strands, spacing them out and lubricating them. The gluten becomes less elastic and much more extensible (like chewing gum).

This is the secret to the crumb: an extensible network allows gas bubbles (CO2) to expand enormously before breaking, creating those large voids we’re looking for.

- Autolyse and Folds: The Science of Patience

With so much water, insisting with a stand mixer (mechanical kneading) is often useless or harmful. It heats the dough and risks “tearing” the network we’re trying to form. The dominant techniques become:

- Autolyse: Leaving water and flour alone for a period (from 30 min to hours). This isn’t “laziness”: in this phase, natural enzymes (proteases) begin to “relax” the proteins, while the water slowly hydrates the flour.

- Folds (Stretch & Fold): These are used to build structure. By stretching and folding the dough, we align the gluten proteins and incorporate air, building the network layer by layer, without mechanical stress.

The “Under the Lens” Tip: Stop fighting the dough. Use time (autolyse, long cold proofing) to let the water bind and folds to organize the structure.

PART 2: The Professional’s Technical Deep-Dive on High Hydration

For the professional, high hydration (H-H) is an exercise in applied chemistry and rheology. Water ceases to be a volumetric ingredient and becomes the regulator of enzymatic activity and dough viscoelasticity.

- Water Activity and Enzymatic Kinetics

In an H-H dough, water activity — the measure of “free” water available for biochemical reactions — is much higher (close to 1). This acts as an accelerator for enzymatic kinetics.

- Amylase (α and β): They become hyper-active. β-amylases produce fermentable sugars (maltose) from the substrate (starch), while α-amylases attack starch at random points, reducing its viscosity (liquefaction).

- Advantage: More simple sugars = more vigorous fermentation (oven spring) and a more intense Maillard reaction (color).

- Risk: If the flour has high amylase activity (low “Falling Number”) and the proofing is long, excessive starch liquefaction leads to structural collapse, making the dough sticky and unmanageable (the “breakdown”).

- Protease: These enzymes (endogenous to the flour) attack the peptide bonds of gluten. In an H-H and acidic pH environment (typical of long, cold maturation), their activity is enhanced. This reduces elasticity and increases extensibility. It’s a delicate balance: too much proteolysis destroys the gas retention capacity of the gluten network.

- Rheology: Hydrogen Bonds vs. Disulfide Bonds

The gluten structure is a 3D network held together by weak bonds (hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds) and strong covalent bonds (S-S disulfide bonds). Water, a polar molecule, acts as the primary plasticizer: it interposes itself between the protein chains (gliadins and glutenins), breaking the inter-chain hydrogen bonds and replacing them with protein-water bonds. This increases mobility and extensibility.

In an H-H dough, structure is no longer built with mechanical force (which would break the bonds), but with time. During folds (S&F) and rest, two processes occur:

- Physical Alignment: The polymers are stretched and aligned.

- Chemical Reorganization: The oxygen incorporated during folds allows the oxidation of free thiol groups (SH), creating new disulfide bonds (S-S). It is these covalent bonds, formed over time, that stabilize the network and give “tone” to an otherwise fluid dough.

The “Under the Lens” Analysis: Managing high hydration means managing enzymatic kinetics (choosing flours with correct rheological and amylase profiles) and promoting the oxidative recombination of disulfide bonds through folds and rests, rather than relying on mechanical development.

The Meeting Point

Water, when used abundantly, radically shifts the baking paradigm. For both the enthusiast and the professional, mastering high hydration pizza dough means the focus shifts from mechanical management of the dough to biochemical management of the process.

For the amateur, it’s the discovery that time and correct technique (autolyse, folds) are more powerful than the stand mixer. For the professional, it’s the mastery of enzymatic activity and rheology to obtain a product that is not just hydrated, but structured, digestible, and has a complex aromatic profile unlocked precisely by water activity.

With unchanging passion and science,

Katia Oldani

Biologist Pastry Chef

Click Here and Visit My YouTube Channel

For any information or to contact me CLICK HERE